Famed for its extremely intense flavour, wasabi is a Japanese plant used as a condiment. It is made by creating a paste from the plants underground rhizome. Wasabi paste is used (sparingly) on dishes ranging from sushi to ice cream. While the foliage and flowers are also edible, they lack the intense flavour of the rhizome and so are not sold commercially.

Wasabi has no history of cultivation in western countries and so the majority of the paste used in restaurants or sold in shops is an ersatz (surrogate) version made by mixing horseradish with green food colouring. However, where true wasabi can be sourced, it costs upwards of £250/kg! Because of this high price and increasing demand, wasabi farms have begun to spring up in Europe and The United States.

Despite being widely reported to be ‘the most difficult plant in the world to grow’, I have never struggled with growing wasabi, so I thought I would pass on some tips I have gained from growing it on a small scale.

Propagation

The main barrier to widespread commercial cultivation outside of Japan is the speed of propagation. Plants will produce numerous inflorescences bearing white crucifer flowers in the Spring. However, viable seed is very difficult to produce, so division is the best form of propagation. I have found that this is best undertaken in March. I cut the inflorescences off once a few flowers have set fruit in the belief (untested) that this satisfies the hormonal requirement to flower, but prevents the plant from diverting significant amounts of resources to producing more flowers and seed pods. I have also dabbled with micropropagating wasabi (see below), and while successful, the weaning phase was problematic.

Cultivation

The reasons wasabi is considered so difficult to cultivate comes from its two absolute requirements; 1) the soil must constantly be kept moist, and 2) at the same time the soil must be extremely free-draining. Therefore, in its natural habitat, and on Japanese farms, it is grown in shallow beds in or next to rivers. In order to satisfy the first requirement in England I have found that it is best to include a high proportion of perlite in the growing media, and grow in tall rose pots that further aid drainage. Then to ensure the growing medium is kept constantly moist I water every day in summer, or hook up all the plants to an automatic irrigation system. Soil moisture is further retained using a layer of mulch, and using fabric shading over the crop in mid-summer as is standard in Japan.

While wasabi is grown in flowing water in Japan, this does not mean it cannot also be field grown on a commercial scale. As is the case with watercress, another riparian species as long as the requirements for a moist free-draining growing medium are met you can grow it anywhere. Obviously clay soils and places without access to irrigation water should thus be avoided.

Other reasons growers may wish to avoid river-based growing systems is the scarcity of the land suitable, and the need to place fertilizer into the river. In Europe, we look to limit fertilizer getting into rivers to prevent eutrophication, so you would be in serious trouble with the authorities if you tried this!

Pests and disease

Luckily, I have not suffered any major pest or disease issues with wasabi. I suspect the lack of pests is because I grow under glass and I am fully expecting the usual pests of brassica crops when I move them outdoors once I have too many to house in the glasshouse. Club root might also be an issue as I transition from organic growing media to soil cultivation.

One minor pest issue has been fungus gnats, due to the requirement to keep the growing media constantly moist, however, this can be effectively controlled by placing thin strips of yellow sticky traps at or near the surface.

The only disease I have encountered was a small patch of powdery mildew in autumn on older leaves.

Cultivars

Being from Japan and called wasabi, it is no wonder its Latin name is Wasabia japonica, although annoyingly the genus also goes by the synonym Eutrema. There are roughly 17 cultivars of wasabi grown in Japan, with each being bred to suit the climate of a particular region, rather than there being unique features about the taste or appearance of each cultivar.

Do not get confused by people trying to sell ‘wasabi-like’ plants on sites such as EBay, or varieties of rocket called ‘wasabi’; none of these will produce rhizomes.

Fertilizer choice

Two fertilizers I would highly recommend for wasabi are liquid gypsum and lime sulphur (calcium polysulphides). This is because, being a member of the cabbage family, wasabi require high levels of calcium and sulphur to thrive. Liquid Gypsum and lime sulphur thus compliment standard NPK fertilizers, which always lack calcium.

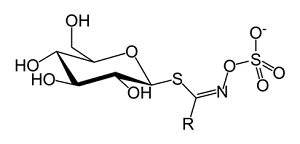

Sulphur is essential for wasabi cultivation because it is component of the glucosinolate molecules that give wasabi their unique flavour. In fact, in crop plants belonging to the Brassicaceae family the level of bitterness is proportional to the amount of glucosinolates present in the tissues. So, on a scale of bitterness according to their levels of glucosinolates brassica crops are ranked;

Radish < cauliflower< cabbage < mustard < horseradish < wasabi

Because glucosinolates readily break down to volatile compounds, it is always advised that wasabi paste is freshly ground each time it is required.

In addition to being the critical factor in determining wasabi’s taste profile, glucosinolates also serve a valuable defensive function for the plant, making them unpalatable to pests and diseases. As such, supplying sufficient sulphur will ensure that the plant can maximise its production of glucosinolate defences.

An additional benefit of liquid gypsum for wasabi cultivation is its ability to flocculate deep into the soil profile, providing much needed drainage.

An additional benefit of lime sulphur is its alkalinity, which will raise the soil pH. A high soil pH is always advisable when cultivating brassica crops, not least for minimising infestations of club root.

For more information on liquid gypsum or lime sulphur please visit the main Plater Bio webpage or get in touch. Do not tank mix either product with NPK fertilizers as insoluble calcium phosphate will precipitate out.

-500-width.jpg)